The novel was first published serialized in Temple Bar, running from October 1872 to

July 1873, and then by Bentley in two volumes on 20 May 1873. Reports about its

success are contradictory. It was a success when first serialized (Peter Ackroyd.

Wilkie Collins, 2012, p149), but did

not sell well in Bentley's first edition (Catherine Peters. The King of Inventors, 1991, p340). Sales

in the US, however were "enormous" (Peters, 1991, p345). Mudie's

Circulating Library demanded that 'Magdalen,' the name for a reformed

prostitute should be removed from the title before the book's publication in

two volumes. Collins refused. Mudie's complaint may have dampened the UK sales

of the novel, or it may have increased them.

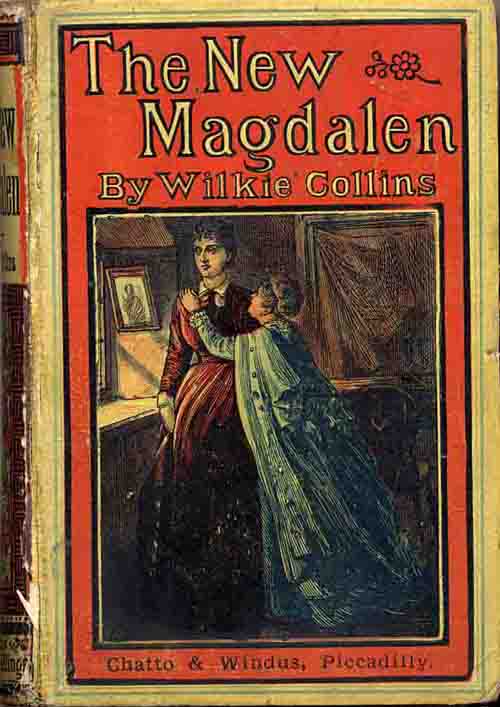

(Image 1889 Chatto & Windus yellowback from http://www.wilkie-collins.info/books_newmag.htm)

(Image 1889 Chatto & Windus yellowback from http://www.wilkie-collins.info/books_newmag.htm)

Collins wrote The New

Magdalen as much for the stage as for the page. Bentley's two-volume

publication came out the day after the theatrical version of The New Magdalen opened in the Olympic

theatre on 19 May, 1873. It was one Collins's most successful plays and ran for

nineteen weeks in the Olympic and toured the country for years. It was also

staged on Broadway, opening 10 November 1873 (several pirated versions had

preceded this) while Collins was on a reading tour in America. According to the

Times, the audience was much affected

and "The sobbing in different parts of the house was painfully

audible." The play was sensational. But it was not universally applauded. "An

outraged lady wrote in the Daily Graphic":

"The author of the New Magdalen

has opened a recruiting office for prostitutes, and has made a direct attack on

virtue and honesty. ... A play so

utterly vicious, so shamefully profligate in its teaching, has never before

been produced at a New York theatre." (Robert P. Ashley "Wilkie

Collins and the American Theatre" in Nineteenth

Century Fiction, Vol. 8, Nr 4, March

1954, p250).

The theatrical quality of the novel is clear from the start:

it is divided into two 'scenes,' both of them opening with 'preambles' listing

the time, the place and the 'persons' involved in the action. The settings are

very limited; the first five chapters making up 'Scene 1' all take place within

the four walls of a cottage on the frontier of a Franco-German war in the

autumn of 1870. 'Scene 2' is limited to the various rooms of Lady Janet Roy's

Maplethorpe House. At the opening of this section, the dining room is described

very much as a stage setting in the present tense:

"[It] is famous among artists and other persons of

taste for the carved wood-work, of Italian origin, which covers the walls on

three sides. On the fourth side, ... a conservatory, forming an entrance to the

room, through a winter garden of rare plants and flowers. On your right hand,

as you stand fronting the conservatory, the monotony of the panelled wall is

relieved by a quaintly-patterned door of old inlaid wood, leading to the

library, ... A corresponding door on the left hand gives access to the

billiard-room, to the smoking-room next to it, and to a smaller hall commanding

one of the secondary entrances to the building. On the left side also is the

ample fire-place ..." (The New

Magdalen, Scene 2, Chapter 6)

The many doors in this setting provide ample opportunities

for making dramatic entrances and exits. The action is made up of dialogue

between characters, usually as a series of meetings between pairs of characters

in the various rooms. There is also a dramatic opportunity for characters to

peer in through open doorways and then withdraw, indicating their presence as

eavesdroppers. On stage this may be necessary, but on a page, this bobbing in

and out of doorways comes across as unintentionally comical (The New Magdalen, chapters 15 and 17,

where Grace Roseberry stalks around Maplethorpe House).

Collins's biographer Catherine Peters notes that both Miss or Mrs? (1871) and The New Magdalen "were

written with dramatization in mind" and because of this "Both suffer

from this literary economy. Wilkie's practiced ingenuity in handling a

complicated story and his impersonations of differing points of view, his great

strengths were jettisoned." (Peters, 1991, p337)

I would argue that the limited setting and abundance of

dialogue are appropriate for the method Collins has chosen to deal with his

topic: The New Magdalen is about the

internal struggle of one woman, Mercy Merrick, to make a choice: to either hang

on to her assumed identity and gain a social position or to resume her true

identity and redeem her soul. The closed setting within Maplethorpe House

reflects the protagonist's claustrophobic internal situation. As the plot

develops she finds herself in one emotional cul-de-sac after another, trashing

desperately within the confines of her own conscience. The numerous dialogues

echo Mercy's inner debates about what she should do. In this way, the setting and

the narrative approach serve the central theme of the novel.

In Mercy Merrick "Wilkie created a vehicle for a clever

actress: several triumphed in the part on stage. In the novel the character

seems hollow and platitudinous. The potentially interesting character of the

elderly Lady Janet, .... though

plausible on stage , is unbelievable to a reader, who has time to think about

her reactions." (Peters, 1991, p338).

Whoever took on the part of Mercy Merrick, would get a

chance to act her socks off. The amount weeping, hand-wringing and dramatic

poses in majestic glory offered by the narrative would satisfy the most

demanding diva. But there is room for other characters to strut their stuff,

too. They get to swear, rant, weep (both leading men burst into tears in their

turn) and despair.

The common complaint about sensation fiction is that it is

all plot and no character. And admittedly, melodramatic posturing and

overwhelming emotion not a plausible character make. However, in The New Magdalen all the character have

some degree of roundness. It may not be anything a la Gustave Flaubert (it is

quite interesting to compare Mercy Merrick to Emma Bovary and see what contrasting

approaches and skills Collins and Flaubert display in their depiction of two

female protagonists), but there is some life stirring within the bosoms of all

main characters.

Grace Roseberry is the wronged, suffering victim but turns

out to be not a very nice person. Horace Holmcroft is the initial

love-interest, handsome hero who gallantly rescues Mercy Merrick. He is also small-minded

and dim-witted and yet very, very respectable and honourable. Julian Gray is

the fire-brand preacher favoured by women, Mercy's spiritual saviour (where Horace

is her physical saviour). His character is an odd combination of fervent

Christian faith and school-boy light-heartedness; and it goes through some

development in the narrative where he begins as an actor enjoying his success

in the pulpit, until a trip to the north and a glimpse of the rural poor cause

him to abandon his glittering career as a preacher for missionary work.

No comments:

Post a Comment