Émile Gaboriau (1832-1873) has a well-recognized position in

the history of detective fiction even if he is read little today (his novels

are becoming available as e-books, but there are no recent printed editions). He

provided inspiration for mystery writers on both sides of the Atlantic; Anna

Katharine Green mentions him in an interview in 1929 (in Bookman, Vol 70, p168) and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle found in Gaboriau's

detective stories a source for Sherlock Holmes. In 1924, Conan Doyle is quoted

as writing in his memoir: “Gaboriau had rather attracted me by the neat

dovetailing of his plots,” (http://sherlockholmesexhibition.com/path-to-baker-street/)

and in an interview in 1900, Conan Doyle explained how he got the idea for A

Study in Scarlet (1887): "it was about 1886 - I had been reading some

detective stories, and it struck me what nonsense they were ..." According

to Pierre Nordon, Conan Doyle's notebooks for 1885 and 1886 show that among

Conan Doyle's reading "almost the only detective stories were by Gaboriau."

(Pierre Nordon. Conan Doyle, 1966, p.

225). In the early pages of A Study in

Scarlet, Holmes dismisses Gaboriau's detective Lecoq as "a miserable

bungler. ... That book made me positively ill." (A Study in Scarlet, Chapter 2). For a more detailed look at traces

of Gaboriau in Sherlock Holmes stories, see for example, http://www.worlds-best-detective-crime-and-murder-mystery-books.com/gaboriauinfluenceondoyle01-article.html.)

In France, even before than in

England, the idea of detective police had captured people's imagination. This

fascination with the detective as an authority moving across class boundaries

and ferreting out the hidden secrets of both respectable and criminal classes,

was quickly harnessed commercially. Eugène

François Vidocq (1775-1857) was a

criminal who became the head of the French detective force Sûreté Nationale

and founded what is generally thought to be the first ever private detective

agency. In 1828 he published his memoirs in four volumes (they were probably

ghost-written). They were a roaring success and gave Vidocq life-long fame. These

memoirs and Vidocq's character, it has been suggested, gave Edgar Allan Poe

inspiration to create Auguste Dupin, who in turn, together with Vidocq,

inspired Émile Gaboriau to come up with M. Lecoq.

(from http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eug%C3%A8ne-Fran%C3%A7ois_Vidocq)

Vidocq was a thief, a fraud and a

womanizer; he was constantly on the run after breaking out from prison and once

dressed as a nun to escape his pursuers. In 1809, after having been caught

again, he turned his coat and became an informant for the police. First he

worked as a prison spy, but after his release in 1811 he became a plainclothes

detective. In 1813 Napoleon Bonaparte

created Sûreté Nationale with Vidocq at

its head. The early 1800s were a turbulent time in France and Vidocq's career

had its ups and downs. He is, however, credited with developing many modern policing techniques (record keeping, ballistics, chemical analysis, crime scene investigation). In 1832 Sûreté Nationale overhauled and Vidocq left. In

1833, he founded his own private detective agency Le bureau des renseignements. Vidocq and his

organization were in constant loggerheads with the official police and he was

plagued by court cases brought against him. Vidocq died in 1857 at the age of

82. He was a well-known public figure and his influence has been spied in the

works of writers like Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac and Alexander

Dumas. For a good summary on Vidocq see Graham Robb's review of the 2003

edition of Vidocq's memoirs in the London Review of Books (http://www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n06/graham-robb/walking-through-walls).

(A full text version of Vidocq's memoirs is available at https://archive.org/details/memoirsvidocqpr00cruigoog).

Gaboriau's books, at the time of publication, were patchily

translated into English; a browse of the catalogue of the National Library of

Scotland shows that a number were published in English in the 1880s, but there

are very few later editions, once those disappeared from print. Gaboriau's

novels would have belonged to that army of yellow-backed, French cheap novels

read for thrills and titillation. It is reasonable to assume that merely the

multitude of mistresses established in luxurious quarters featured in these

tales would have created a pleasurable sense of naughtiness for their English

readers.

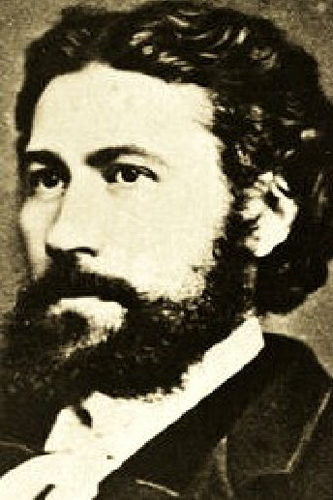

Emile Gaboriau (from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%C3%89mile_Gaboriau.jpg)

Gaboriau was born in the village of Saujon,

Charente-Martime. In 1855 he moved to Paris, where he worked as a journalist

and a writer for magazines. According to Encyclopedia Britannica,

"Gaboriau’s prolific imagination and acute observation generated 21 novels

(originally published in serial form) in 13 years. He made his reputation with

the publication in 1866 of L’Affaire Lerouge (The Widow Lerouge)

after having published several other books and miscellaneous writings." (http://www.britannica.com)

In this novel (also translated as The Lerouge Affair) Gaboriau created police detective M. Lecoq and

amateur detective Père Tabaret. Other detective stories, featuring the same

serial detectives, followed in quick succession: Le Crime d'Orcival and Le Dossier n° 113 both in 1867 and

two-volume adventure of Monsieur Lecoq

(L'Enquête and L'Honneur du

nom) in 1869. Altogether, Lecoq appears in ten novels in one short story (http://www.pjfarmer.com/woldnewton/Lecoq.htm,

this site offers a detailed look at the character).

It is generally

appreciated how Gaboriau's detectives are masters of both disguise and sharp,

analytical thinking. Commentators tend to emphasize those features of

Gaboriau's stories (plot twists and clues) and his characters (minute

observations and the deductive method) which lead in a straight line to

Sherlock Holmes and the classic detective story (see, for example, http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/gaboria.htm,

for more on Gaboriau and detective fiction). Less attention has been paid to

Gaboriau as a writer of sensation fiction.

In the middle of

his well-known detective novels, in 1868, Gaboriau published another two-volume

novel Les Esclaves de Paris, translated as The Slaves of Paris.

The two volumes were entitled Caught in the Net and The Champdoce

Mystery. The Slaves of Paris

does not follow the pattern of earlier Lecoq-novels with a detective character investigating

a crime or solving a mystery. It is, however, a sensation novel.

The Slaves of Paris is

a story of a cunning plot of manipulation and deception created and

orchestrated by criminal mastermind Baptiste Mascarin. It is a tale told as

much from the point of view of the scheming villain as from that of his innocent

victims. It is a thrilling drama of love and money and, perhaps most of all,

love of money. M. Lecoq appears in the story, but only in chapter 32 (of 35

chapters) of The Mystery of Champdoce.

The master criminal and his creator are clearly aware of the

sensational genre within which they both operate. When Mascarin explains the course

of his dastardly plot to his henchmen, he ends by commenting that it "... would really make a good sensational

novel." (Caught in the Net,

Chapter 18).

We may agree with the general view of Vidocq's influence on the analytical, methodical

detective work carried out by Lecoq (Dupin and Holmes), but I will also suggest that we can see traces of Vidocq's life of crime (frauds, false identities, cunning plots) in the characters of Mascarin and his gang in Gaboriau's The Slaves of Paris. This time, Vidocq is not a source of ratiocination and the scientific method of detection but a source of excitement, menace and sensation.

No comments:

Post a Comment